Our Story – The Journey of the EUF

Introduction

Before the European Ultimate Federation (EUF) was officially founded, European Ultimate was powered by passionate volunteers, informal agreements, and sporadic tournaments. What began as a loose network of players and self-organized events grew into a structured, policy-oriented, and professional federation. The following story captures that journey: how individual enthusiasts laid the groundwork for a continental community, how key figures formalized governance, and how the federation evolved into a respected organization with global relevance. It also reflects on the interplay between the World Flying Disc Federation (WFDF), national federations, and the volunteers who turned passion into policy.

Personal Beginnings (Late 1980s–1990s)

Many early European Ultimate pioneers discovered the sport by chance, guided more by curiosity than by structure. In 1987, Ted Beute was a sports student in the Netherlands when classmates returned from a national Frisbee championship. Curious, he joined their practices—small hall sessions filled with running, laughter, and defensive intensity. Within months, his team unexpectedly won a national indoor title. Ted recalls those early years as “jogging and running without much strategy,” yet the athletic freedom and self-refereed spirit hooked him immediately.

Meanwhile, in Bologna, Andrea Furlan discovered Ultimate in the early 1990s through Rimini and Puerto Rican players who practiced behind his university’s physics department. Coming from volleyball, Andrea was fascinated by the open culture and the spirit-based competition. His first tournament—a snowy weekend in Geneva—showed him that Ultimate wasn’t just a sport, it was an international community. Within a few years, he joined Bologna’s La Fotta and helped shape what would become one of Europe’s most influential Ultimate hubs.

By the mid-1990s, Andrea was organizing local tournaments in Bologna, later expanding across Austria, Slovakia, Hungary, and the Czech Republic. He helped establish the Central European Ultimate League, which linked multiple countries in monthly competitions and a season-ending final. These regional circuits emphasized low costs, high participation, and the joy of cross-border friendships. Ted, meanwhile, became a key organizer in the Netherlands, managing national competitions from 2000 onward and later serving on the board of the European Flying Disc Federation (EFDF). Both men’s paths illustrate how early players grew into the sport’s architects.

Before the Official Founding of the EUF

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, European Ultimate revolved around irregular tournaments such as the European Ultimate Club Championships (EUCC) and the European Championships for national teams. These events depended on local initiative rather than central coordination. The EFDF nominally oversaw continental flying disc sports but was never a strong, legally defined body. Yet, within its loose structure, important groundwork was laid by volunteers like Thomas Griesbaum, Alia Ayub, Paul Eriksson, Adam Batchelor, and later Ted Beute. They maintained communication between nations, facilitated committee meetings, and upheld WFDF standards across Europe.

By the early 2000s, the European community began calling for more structure. The 2003 EFDF meeting in Fontenay brought the issue to the forefront: elite clubs wanted regular, merit-based continental competition instead of occasional four-year cycles. Among those leading this charge were Andrea Furlan, David Brucklacher, Sy Hill, and Roo, who collectively envisioned a “Champions League”-style structure—an annual, reliable series that would raise the level of play and unite Europe’s best teams.

The European Ultimate Club Series (2006–2009)

That vision became reality in 2006, when the European Ultimate Club Series (EUCS) launched with its first finals in Florence. Using rankings from the 2005 Rostock European Championships, sixteen top men’s teams and eight women’s teams qualified. Andrea recalls the thrill of seeing major clubs—Clapham (UK), Ragnarok (Denmark), FAB (Switzerland), and Big Easy (Austria)—face each other in a structured continental format. Vienna’s women placed third, and Clapham’s dominance began a dynasty that continues today. The event wasn’t just a tournament; it was a statement that Europe could organize itself at a professional standard.

The EUCS expanded quickly, formalizing qualification through regional tournaments and introducing XEUCF (Extended EUCF) to maintain an open, inclusive model alongside elite competition. Behind the scenes, Andrea, Ted, and others discussed transforming EFDF’s informal network into a dedicated governing body for Ultimate. The groundwork was laid for a new federation—one that could combine grassroots enthusiasm with clear policy and accountability.

The Founding and Early Years (2009–2019)

At XEUCF 2009 in London/Nottingham, national representatives and EFDF committee members met to chart the future of European Ultimate. The consensus: create a new entity focused solely on Ultimate, with proper statutes, membership, and legal recognition. Andrea Furlan was elected president and tasked with drafting bylaws and forming the European Ultimate Federation (EUF). Over two years, he coordinated feedback from clubs and federations, consulting legal experts in Austria. The bylaws were officially approved at the 2011 European Championships in Maribor, and by 2012, EUF was registered as a legal non-profit association in Austria.

The early EUF board included a president, secretary, treasurer, and directors for Open, Women, Youth, Masters, and Spirit of the Game. Committees took on practical responsibilities—developing qualification systems, event standards, and communication processes. EUF’s guiding philosophy was simple: organize competitions for clubs, foster cooperation between federations, and ensure every athlete could compete regularly at a meaningful level.

During these years, the relationship with WFDF evolved. Initially, WFDF wasn’t sure how EUF fit within the global structure. EFDF technically remained WFDF’s European affiliate, while EUF began taking over Ultimate-specific work. Under leaders like Nadia Brown, WFDF professionalized and clarified continental relationships. By 2015, both organizations cooperated seamlessly—WFDF managing global championships and governance, and EUF focusing on Europe’s growth.

Copenhagen 2015 – A Key Milestone

The 2015 European Championships in Copenhagen became a defining moment for EUF. Supported by the Danish federation and national sports authorities, and led operationally by Karina Warden, the event demonstrated EUF’s capacity to host at a professional standard. Top-quality fields, on-site branding, dignitaries including the Danish sports minister, and comprehensive live streaming through a Finnish production team turned the tournament into a showcase. Andrea recalls it as “the first time ambassadors and politicians saw Ultimate as a legitimate sport.” It was also strategically timed just before WFDF’s presentation to the IOC, helping secure disc sports’ recognition.

Professionalization and Paid Roles (2016–2020)

After Copenhagen, EUF entered the media and streaming era. Partnering with Finnish platform Fanseat, EUF ensured continuous coverage of events such as Tom’s Tourney, Vienna Spring Break, and the EUCF finals. The platform invested heavily—Andrea recalls roughly €50,000 annually—to build an audience for Ultimate. While the paywall model limited reach, the experience taught EUF valuable lessons about content creation, sponsorship, and storytelling.

By 2018, EUF experimented with part-time contractors. Martin Montes managed the Fanseat partnership, followed by Will Foster, who handled graphics, communications, and social media. Recognizing that volunteer energy alone could no longer sustain the workload, EUF sought funding for stable staffing. In 2019, the federation secured a €55,000 Erasmus+ grant to support strategic development, process documentation, and structural planning. This allowed the hiring of Felix Nemec as EUF’s first paid employee—a turning point in the federation’s operational maturity.

The Pandemic and Strategic Growth (2020–2025)

When the COVID-19 pandemic halted competition, EUF used the opportunity to strengthen internally. With Felix leading operations and Andrea continuing as president, the federation focused on digitizing processes, building documentation, and clarifying roles. The Strategy 2025 initiative emerged from this work, outlining long-term goals for sustainability, inclusivity, and financial stability. EUF also began onboarding additional part-time staff to support communications, competition management, and governance—laying the groundwork for professional continuity.

During this period, EUF reaffirmed its commitment to youth development, continuing the legacy of early pioneers like Chris Dehnhard and Mark Kendall, who had organized junior European Championships for years under EFDF. By bringing youth programs formally under EUF’s governance, the federation ensured consistency and visibility for the next generation of players.

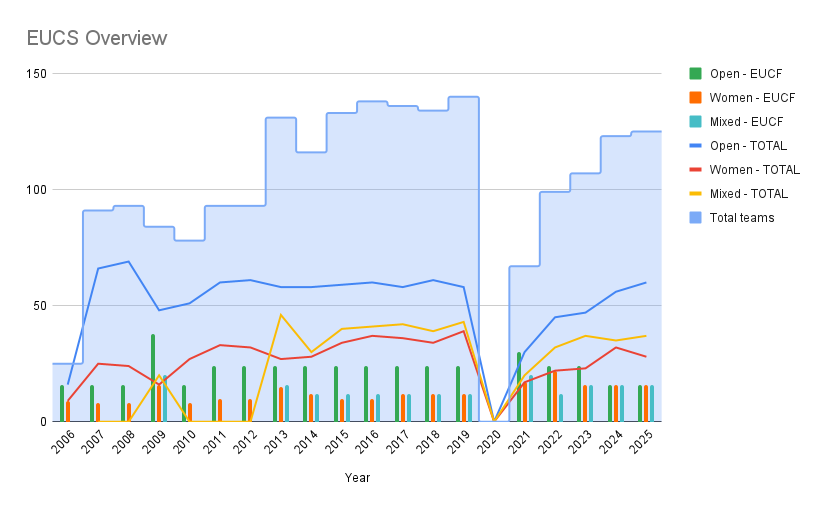

The graphic below shows the growing numbers connected to the EUCS participation.

Reflection and Future Perspectives

Looking back, the evolution from informal tournaments to a structured federation represents a remarkable achievement. Key milestones include the launch of the EUCS in 2006, the formal founding of EUF in 2011, the professional breakthrough in Copenhagen 2015, and the first full-time hires by 2019. Each stage marked a deeper level of stability and ambition.

EUF’s relationship with WFDF has matured into a partnership of equals—Europe manages its own competitions and development while aligning with global rules and values. National federations have grown stronger in parallel, providing grassroots development and feeding talent into continental events. The tri-layer structure—WFDF globally, EUF continentally, national bodies locally—now offers clarity and collaboration.

The next challenges lie in commercial partnerships, media visibility, and long-term funding. Regular broadcasting, consistent branding, and a stronger sponsorship base will allow EUF to sustain growth while preserving Ultimate’s culture of inclusivity and fair play. Future leaders are advised to maintain that balance: professionalism without losing the spirit.

Conclusion

From snowy Geneva fields to the grand stage of Copenhagen, from living-room organizing sessions to international livestreams, the European Ultimate Federation’s story is one of evolution through collaboration. As Andrea Furlan, Ted Beute, and Felix Nemec each emphasized, EUF’s success has always depended on trust, dialogue, and the drive to make Ultimate accessible to all. What began as a handful of volunteers with borrowed discs has become a continental institution—proof that with shared purpose, even a niche sport can build a professional, community-rooted future for generations to come.